RAYYANE TABET: ALIEN PROPERTY at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This article was originally published in The Brooklyn Rail

Seated figure, Neo-Hittite, c.10th–9th century BC (reconstructed 2001–10), Tell Halaf (ancient Guzana), Syria. Basalt, 75 5/8 x 32 1/4 x 39 3/8 inches. Max Freiherr von Oppenheim Foundation, Cologne.

Early one morning, sometime around the 1890s, a Bedouin tribe went to bury one of its elders on a hill at the border of Syria and Turkey. While digging his grave, they came upon a large stone sculpture of an animal with a human head. Scared and taken aback, they covered it up and went to look for another burial site. Their land suffered from unprecedented drought that year, along with a cholera outbreak and swarms of locusts. The tribe attributed these misfortunes to evil spirits that had been released when the statue was unearthed. When Max von Oppenheim—a German diplomat then living in Cairo—arrived in the village of Tell Halaf in the summer of 1899, the Bedouins told him the story of gods, demons, and monsters hiding underground. They hoped that his curiosity would lead him to dig up the statue so that the curse would be carried away from them. His interest was sparked, and for the next 30 years, von Oppenheim kept coming back and excavating Tell Halaf.

In its new exhibition Rayyane Tabet: Alien Property, the Metropolitan Museum of Art explores the circuitous route that ancient artifacts sometimes travel to wind up on display in a hallowed Western institution, if they aren’t first destroyed or lost. On view in the Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art are four stone reliefs dating back to the ninth century B.C.—the same ones discovered by the Bedouins in the early 1900s at Tell Halaf. The stone slabs are quite remarkable in and of themselves: One features an image of a horse-drawn chariot hunting a lion; others show fantastic creatures and scenes of regality, combat, and ceremonial banquets. These slabs that once embellished the walls of a monumental Neo-Hittite palace now serve as far-flung time capsules that bear witness to the geopolitics of the mobility of ancient artifacts.

It is, as framed by the artist Rayyane Tabet, a “spy story.” In 1929, the governing authorities of the French Mandate stationed in Lebanon sent Tabet’s great-grandfather Faek Borkhoche to be the secretary to the German excavation director Max von Oppenheim, and to gather information on the archeological dig he had been carrying out in Tell Halaf. At the time, German intelligence officers disguised as ethnographers or archaeologists were sent on sham survey missions in the region. The French suspected that von Oppenheim was one of these officers, since he had been going back to the same location on the border between Syria and Turkey. Faek Borkhoche’s job was essentially to spy on a suspected spy. He wrote reports detailing von Oppenheim’s activities and sent them back to Beirut along with photographs, which later landed in the possession of his great-grandson, Rayyane Tabet.

194 orthostats, or stone slabs carved in low relief, were discovered in 1911. In 1929, authorities under the French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon began to divide and allocate the archaeological artifacts that had been discovered at Tell Halaf. Von Oppenheim received the bulk of the findings, about 80 orthostats. He traveled to the United States in 1931 with the intention of selling eight of the reliefs, but he was unsuccessful, so he left them in storage in New York, with the intention of retrieving them. However, shortly after the United States entered World War II, the government reactivated the Alien Property Custodian Act. By early 1943, the agency’s research into the property of German nationals had led to the storage facility that housed von Oppenheim’s reliefs. American authorities confiscated them after deeming them “enemy property,” at which point they were bought by the Metropolitan.

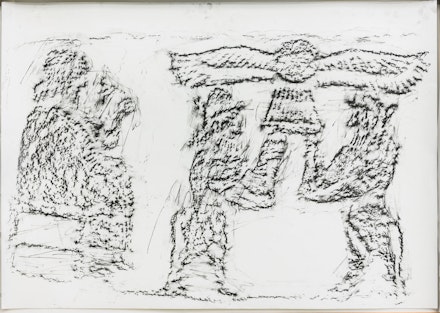

Rayyane Tabet, Orthostat #170 (detail) from “Orthostates,” 2017–ongoing. Framed charcoal on paper rubbing. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Bequest of Henrie Jo Barth and Josephine Lois Berger-Nadler Endowment Fund, 2019.

In 2017, Tabet began making rubbings of the existing orthostats. So far, he has created rubbings of 32 basalt reliefs in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin; the Louvre Museum, Paris; the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; and the Metropolitan. Here, the installation of the rubbings echoes the placement of the original stones along the niched walls of the palace. Above them is a complete list of the original orthostats, citing the current location, medium, and motif. In comparison to the definitive and majestic solidity of the stone artifacts, Tabet’s mournful etchings seem to exude a more ambiguous quality that’s decidedly modern. The charcoal rubbings may seem like mere tracings, but the artist doesn’t appear to be aiming to duplicate the reliefs’ designs; rather, he’s reinterpreting the creative output of a long gone civilization, while paying tribute to their subsequent history of plunder and redistribution.

Installation view: Rayyane Tabet / Alien Property, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2019-2021.

In Genealogy (2016), an installation of five segments of goat-hair rug, Tabet presents a different layer of Borkhoche’s story. When Tabet’s great-grandfather died in 1981, he left behind a goat-hair rug given to him by the Bedouin of Tell Halaf in 1929. It was his wish that the 65 foot-long rug be divided equally among his five children, with the request that they in turn divide it among their children, and so on, until the rug eventually disappeared. As of today, the rug has been divided into 23 pieces across five generations. Here, Tabet has borrowed five segments of the heirloom from family members and arranged them in the form of a genealogical table, with the oldest generation at the top. The pieces on display here illustrate the equal segmenting and dissemination of the rug amongst generations: the smaller the fragment, the further it has been handed down. Tabet’s artistic practice draws from experience and self-directed research, he explores stories that offer an alternative understanding of major socio-political events through individual narratives. Informed by his training in architecture and sculpture, his work investigates paradoxes in the built environment and its history by way of installations that reconstitute the perception of physical and temporal distance.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rayyane Tabet: Alien Property

October 30, 2019 – January 18, 2021