HOWARDENA PINDELL

Autobiography

at Garth Greenan Gallery

Howardena Pindell, Autobiography: Fire (Suttee), 1986–1987. Mixed media collage on paper, 90 x 56 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

In 1979, Howardena Pindell (b. 1943) had yet to turn 40 when a traumatic car accident interrupted her career. Cofounder of the pioneering feminist gallery A.I.R. and one of the first black women to be appointed curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Pindell was also an artist. When she began working at the MoMA in 1967, in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, Pindell had begun spending her nights creating her own pieces, drawing inspiration from many of the shows hosted by the museum. Her work explored texture, color, structure, and the process of making art. It also was often political, addressing the intersecting issues of racism, violence, exploitation, and feminism. The artist had cultivated a signature painting style: abstract canvases with colorful paper circles attached to neutral backgrounds, mashed with thick, protruding brushstrokes of paint combined to produce an effect like confetti sprinkled over a sidewalk. The crash left her with acute memory loss, but the years following her rehabilitation literalized a process of destruction and reconstruction in the artist’s work. Howardena Pindell: Autobiography, currently on view at Garth Greenan Gallery in Chelsea, presents a handful of paintings and mixed media works on paper from the artist’s “Autobiography” series, created between 1980 and 1995, when she plumbed her life and recollections in an effort to help herself heal.

Pindell had already been a tireless and diligent photo and postcard collector for decades. After the accident, these relics revealed their full usefulness to the artist. The first of the series, Autobiography: Oval Memory #1 (1980-1981) reflects Pindell’s initial attempts to amalgamate memories following the accident. Pindell cut images from her collection into strips before positioning them on the collage. She alternated between photographic imagery and acrylic paint, and integrated the printed fragments into layers of pigment and paper. The swirling combination of postcards, images, paint, and cibachrome forms a polyphony of perspectives—one that speaks to this period of the artist’s life when she was attempting to uncover and rebuild her memory.

Hole-punched circles of paper meticulously attached to unstretched canvas are signatures of her work. Sometimes, the circles are caked together using globs of paint. Cutting and sewing strips of canvas into swirling patterns, she builds up the surfaces in elaborate stages. In Autobiography: Fire (Suttee) (1986-1987), Pindell used her own body as the focal point, referencing her silhouette on an irregular ovoid canvas by cutting and sewing a traced outline of herself onto its surface. Alluding to an ancient South Asian practice known as Suttee or “widow burning,” painted fingers of various colors (shades of red, yellow, and orange) overlap frantically with strips of photographic fingers all set atop a flame-blue background. The repetition of forms creates a vibrating, fractured feeling. This particular work can be seen as a form of purging: the artist is perhaps offering her own body and old self for sacrifice, same way as Suttee’s fire —which bears resemblance to the artwork itself—swallows the widow.

This particular period in the artist’s life was marked by reflection, influences, and changes in her path. Pindell has described being deeply influenced by the Black Power and feminist movements, as well as by exposure to new art forms during her tenure at MoMA and her travels abroad, particularly to Africa during the 70s, which were funded by the museum’s International Council. She became fascinated by African sculpture, and began to mirror the practice of three-dimensional accumulation in her own work. African art frequently embraces the use of objects in sculpture such as beads, horns, shells, hair, and claws, and these materials also informed Pindell’s work. She began to incorporate additional elements like paper, glitter, acrylic, and dye into her collages. The works on view echo the uncanny resonance between the artist’s embodied experience and her formal interests in fragmentation and integration.

Howardena Pindell, Autobiography: Japan (Hiroshima Disguised), 1982. Mixed media collage on paper, 60 x 118 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

Patterns of rupture and healing are overtly present in Pindell’s life story: her sense of self as an African-American, and being a composite of many cultures and backgrounds (her heritage includes African, European, Seminole, Central American, and Afro-Caribbean roots, along with her position as ethnically Jewish, raised Christian) come together with her fascination with science, mathematics, and rationality on the one hand and her interest in spirituality, traditions, and rituals on the other. This synthesis is apparent in Autobiography: Japan (Hiroshima Disguised) (1982), one of the earliest works of the series. The artist created a composite of ten separate pieces that together form one artwork. Informed by the way a nuclear bomb shatters a geographical place, Pindell represented her own life that had been shattered by her memory loss. The ten irregular shapes are hung side by side, but unlike other works in this gallery, they are not stitched or bound together. This speaks to Pindell’s healing process: she found her mind and subsequently her life scattered around, and slowly began to piece them together. In Japan (Hiroshima Disguised), the elements started off separate, but then in later works she began to closes the distances, until the elements eventually fused.

Howardena Pindell, Autobiography: Red Frog, 1982. Mixed media collage on paper, 60 x 118 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

As Pindell ventured further into abstraction, the circle remained a constant shape. In a 2014 interview with ARTnews, the artist recalled a memory from the 1950s when, driving through Kentucky with her father, she spotted a root-beer stand where every mug had a red circle on its bottom. Asking her father about the meaning of the red circle, he responded that the circles were used to segregate the drinking cups because “we’re black and we cannot use the same utensils as the whites. I realized that’s really the origin of my being driven to try to change the circle in my mind, trying to take the sting out of that.”

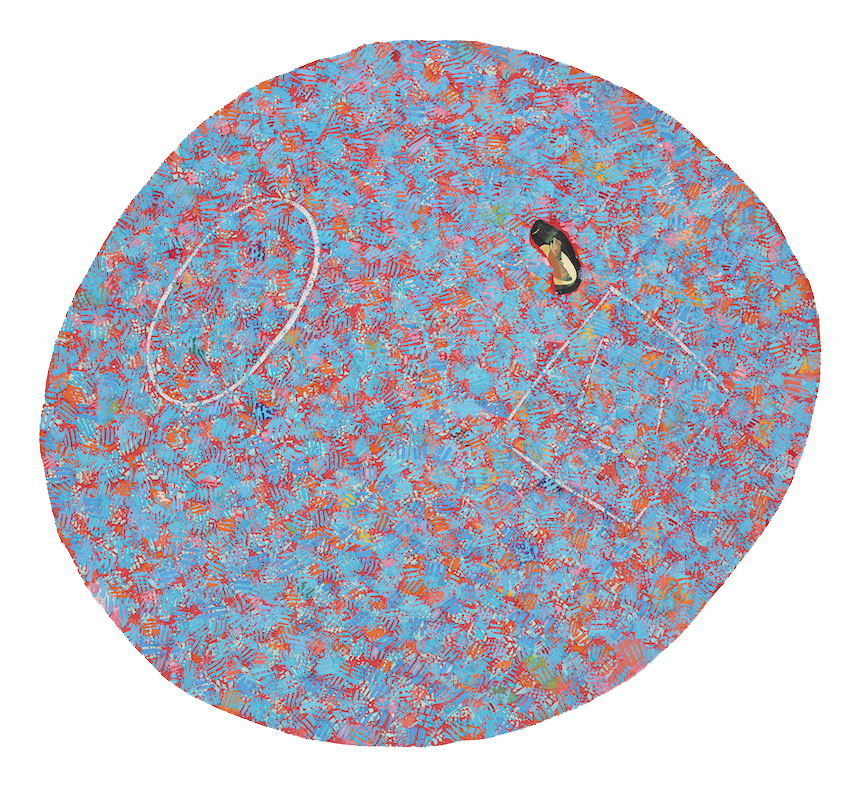

The large-scale works on view in Howardena Pindell: Autobiography have the effect of looking totally flat and white from a distance but actually being made up of tiny dots (or circles) of colored paper, sequins, and paint. Pindell has likened this experience of viewing her paintings to whitewashing her own identity to make it more palatable for the art world. However, her thick-layered paint strokes tell a different story: they are loud, daring, and very much present. Her adoption and reconstruction of the circular shape additionally reinforces this resistance. In this exhibition, Autobiography: Africa (Red Frog II) (1986) comes closest to being a true circle. Bearing within it a red frog, a stitched oval shape, and short and thick brushstrokes of paint, the piece functions as portal to a different iteration of the artist’s life and history—one where she was younger, on the road, inquiring about the red circles.

Howardena Pindell: Autobiography remains on view through December 7, 2019 at Garth Greenan Gallery, 545 W 20th St, New York.